|

© Thomas Tobin

2006, 2013

The

Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome (MRLS), the Septic Penetrating Setal

Emboli Pathogenesis thereof and Recently Reported Caterpillar Related

Abortions in Camels

Thomas Tobin, MVB, MSc, PhD, MRCVS, DABT,

Professor of Veterinary Science and Professor,

The

GraduateCenterfor Toxicology,

The

MaxwellH.Gluck

EquineResearchCenter

Universityof

Kentucky

Lexington

,Kentucky40546-0099

www.thomastobin.com

and

Dr.

Kimberly Brewer, DVM

1711 Lakefield North Court

Wellington

Fla

33414

OVERVIEW:

THE MARE REPRODUCTIVE LOSS SYNDROME (MRLS)

In three weeks around Derby Day, May 5th, 2001,

Central Kentucky

lost one third of its in utero foal crop to the Mare Reproductive

Loss Syndrome (MRLS). Total losses were estimated at $500 million. MRLS

was characterized by minimal clinical signs in affected mares,

relatively non-specific bacterial infections in aborted fetuses, and was

also associated with a very small number of highly unusual unilateral

uveitis cases. Investigations

were immediately begun to determine the cause/s of this syndrome.

Infectious causes were ruled out early. Field and epidemiological

studies linked the syndrome to a coincident epidemic of Eastern Tent

Caterpillars (ETC), suggesting a toxin driven syndrome. Numerous

candidate environmental toxins were investigated and ruled out; then,

when the seasonal ETCs became available in April of 2002, they were rapidly shown to

produce Early and Late Fetal Losses (EFL and LFL) in pregnant mares.

Working with the late fetal loss model we saw our first fetal

losses at three days after our first 50 g/day caterpillar administration.

We

immediately abandoned the toxin hypothesis and assigned a primary

abortifacient role to the bacteria; the question then became how

exposure to the caterpillars caused bacteria to enter the fetal

membranes.

Electron Micrographic (EM) studies in the summer of 2001 had

shown the ETC setae (hairs) to be barbed. We therefore considered the

possible outcomes if small numbers of barbed setal fragments penetrated

the intestinal tract, entered intestinal blood vessels, and then

re-distributed following cardiac output. Penetration

of fetal membranes by these distributing/distributed septic setal

fragments/emboli would directly introduce bacterial contaminants into

the fetus, where they would proliferate unchecked by the immature fetal

immune system. This

probabilistic model immediately explained the early and late fetal loss

events, and also the relatively rapid onset of late fetal losses, and most importantly, the

unique unilateral uveitis cases occurring in

horses of any age or sex. This

biologically unique model, identified on July 10th, 2002, we named the Septic Penetrating Setal Emboli

(SPSE) Model of MRLS and

it was immediately communicated to selected colleagues.

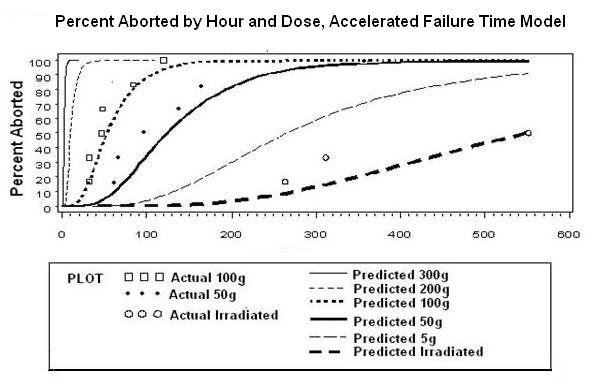

Replication of the LFL abortions in 2003 using a higher (100 g/day) dose

of caterpillars and a similar dose of irradiated caterpillars enabled us

to demonstrate that the LFL abortions follow a unique probabilistic

statistical model elucidated by Accelerated Failure Time analysis.

Furthermore, this model showed that the initial intensity of the

abortion response was exponentially related to the caterpillar dose; at

high doses of caterpillars exposed mares abort very rapidly, while the

caterpillars are underfoot, as had happened in Kentucky in 2001. On

the other hand, at lower doses the abortions are delayed and many

abortions occur after the caterpillars have dispersed, obscuring both

the role of the caterpillars and their relationship to the syndrome.

This highly significant probabilistic mathematical analysis underlying MRLS

was developed soon after Memorial Day, 2003.

These unusual mathematical characteristics of MRLS strongly supported our

proposed Septic Penetrating Setal Emboli model. Then, in the fall of

2003, colleagues necropsying pigs that had been dosed with ETC observed

numerous intestinal microgranulomas encasing setal fragments. These

setal fragments are septic penetrating setal fragments that did not

enter blood vessels; as such these findings provided substantial

histological evidence in direct support of our septic penetrating setal

emboli hypothesis. Similarly,

colleagues dosing rats with ETC in 2001 had observed but not

communicated their identification of similar intestinal microgranulomas

containing setal fragments, as presented here.

This simple septic penetrating setal mechanism is obviously a defensive

mechanism of the caterpillar, and likely a very ancient one. Review of

this proposed mechanism immediately suggests that other caterpillar

setae or indeed any mechanically equivalent structure should produce

similar syndromes. More

recently a syndrome closely related to MRLS named Equine Amnionitis and

Fetal Loss (EAFL) has been identified in

Australia. It is associated with

exposure to processionary caterpillars, and administration of

processionary caterpillars has been shown to abort pregnant mares. Since

then, this and apparently similar caterpillar related field and

experimental abortions have been shown to be associated with

caterpillars, including Eastern Tent Caterpillars (ETC) in Kentucky (

02, 03) and Florida (06) and other caterpillar species in Australia

(March, 05) and Florida (September, 05). Additionally,

recent reports by Volpato and Di Nardo and their colleagues (2013) make

clear that exposure to/ingestion of caterpillars by pregnant camels has

long been recognized as a cause of camel abortions in camel pastoralist

communities in the Western Sahara.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE “SEPTIC PENETRATING SETAL EMBOLI”

HYPOTHESIS

OF MRLS, 2002

The proposed septic penetrating setal emboli based pathogenesis of

MRLS, first conceived in July 2002, explains many of the unique clinical and

epidemiological characteristics of MRLS. The late term fetus is the largest mass of immunologically poorly

protected tissue in the mare; as such it is a large and highly

accessible and vulnerable target, explaining the very rapid onset of

experimental late term fetal losses. The

early fetus is a smaller target, but when accessed by a septic

penetrating setal fragment is equally vulnerable. The eye is a very

small target indeed, explaining the very small number of affected eyes. Additionally,

the uniquely unilateral nature of the eye lesions is consistent with and

in fact requires the uniquely quantal nature of the septic penetrating

setal emboli hypothesis. This hypothesis was shared on a confidential

basis with selected colleagues within hours of conception, then with a

somewhat broader group of colleagues and selected administrators the

following Monday and soon thereafter at the late July 2002 Bain Fallon Lectures,

The Gold Coast,

Australia.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION #1:THE UNIQUE MATHEMATICS OF

MRLS, 2003

The following year (May 03) more LFL abortion rate data

became available and working with Dr. Marie Gantz of the Dept. of

Statistics we showed that experimental LFL closely follows a unique

probabilistic mathematical model called Accelerated Failure Time

analysis. This unusual mathematical signature is consistent with the

unique clinical data, the probabilistic nature of the proposed septic

penetrating setal emboli hypothesis, and the unusual field epidemiology

of MRLS. As such, these

findings were rapidly written up and submitted for publication as a paper

on the toxicokinetics of MRLS (Sebastian et al., 2003). Additionally, because the septic penetrating setal emboli

hypothesis was viewed with skepticism by some of our colleagues, this first

paper was drafted avoiding a direct presentation of our underlying

septic penetrating setal emboli hypothesis. However,

US Copyright for a document describing the overall hypothesis (Copyright#TXU1111484:

2003) was registered with the Library of Congress, June 17, 2003, and a paragraph describing the SPSE

hypothesis was added to the paper prior to publication.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION #2:

IDENTIFICATION OF THE INTESTINAL MICROGRANULOMAS CONTAINING SETAL

FRAGMENTS, 2003

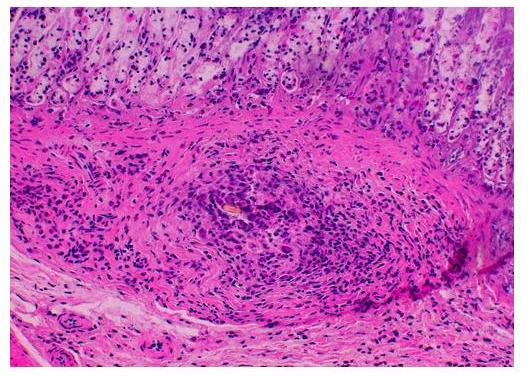

While this Toxicokinetic paper was under review (Fall 2003) we

learned that colleagues performing necropsies on ETC dosed

pigs had observed multiple intestinal microgranulomas in these animals,

each containing a minute central setal fragment. These setal fragments

represent septic penetrating setal fragments that have penetrated the

intestine but which did not penetrate blood vessels to become septic

penetrating setal emboli. Rather, they became encapsulated in intestinal

microgranulomas fully consistent with the first intestinal penetration step of

this proposed hypothesis. Colleagues

at the State University of New York at

Cortland kindly made similar slides available to us from some ETC dosing

experiments on pregnant rats, as presented in this communication.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION #3: LACK

OF CLINCAL SIGNS IN AFFECTED MARES

An unusual aspect of MRLS is the lack of clinical signs in affected

mares and the inability to culture bacteria from the bloodstream of MRLS

mares. The unique eye data

allowed us to estimate the actual number of circulating setal fragments

in MRLS mares. Based on

these calculations it appears that the number of setal fragments

actually distributing in an MRLS mare is very small, likely less than

ten/day in field cases. This

finding explains the lack of clinical signs in affected mares and the

apparent inability to culture bacteria from the blood of clinical and

experimental MRLS mares.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION #4:THE UNIQUE PLACENTITIS OF

MRLS

More recently, the placentitis associated with late fetal loss has

been recognized by our colleagues as pathologically unique and we

believe entirely consistent with this proposed pathogenesis of MRLS, namely the

septic penetrating setal emboli or setal hypothesis of MRLS.

2013: SUPPORTING INFORMATION #5:

CATERPILLARS RECOGNIZED AS THE CAUSE OF OTHER ABORTIONS,

INCLUDING CAMEL ABORTIONS

An immediate (July 10th, 2002

) conclusion from this proposed pathogenesis was that mechanically

and bacteriologically equivalent barbed setal fragments (or mechanically equivalent structures)

from any source should reproduce the

syndrome. As of January

2013, the world score for caterpillar related equine abortions included

Eastern Tent Caterpillars (Malacosoma Americana) from Kentucky,

Northern Michigan (02) and Florida (06), Processionary caterpillars (Ochrogaster

lunifer) in Australia (March 05), Gypsy Moth Caterpillars (Lymantria

dispar) in an experimental challenge in Kentucky (03?) and, in

September 05 in Florida, field abortions reportedly associated with

Walnut Caterpillars (Datana integerrima). Finally,

and most interestingly, there are recent reports by Volpato and

Di Nardo and their colleagues (2013) making clear that exposure to or

ingestion of

caterpillars has for long been known, and unequivocally ("everybody

knows") recognized as

a cause of abortions in camels among several groups of nomadic camel

pastoralists in the Western Sahara, consistent with an earlier report

suggesting caterpillars as a cause of abortions in camels (Bizimana,

1994).

1. THE MARE REPRODUCTIVE LOSS SYNDROME (MRLS)

During three weeks around May 5th 2001

,Central Kentucky

abruptly lost 20% to 30% of its in-place foal crop. Of

foals conceived in the spring 2001, about 2000 were lost, the so-called

Early Fetal Losses (EFLs). Of

foals conceived the previous spring and then close to term, at least 600

were lost, the so-called Late Fetal Losses (LFLs). Based

on these overwhelming reproductive losses, the syndrome was named the

Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome, or MRLS. The

total economic loss for the 2001 MRLS season to

Kentuckyand the breeding and racing industry was initially estimated at greater

than $330 million. MRLS, as

such, had never previously been recognized.

|

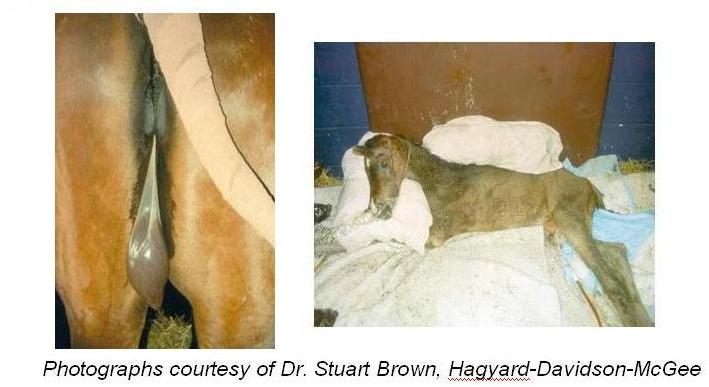

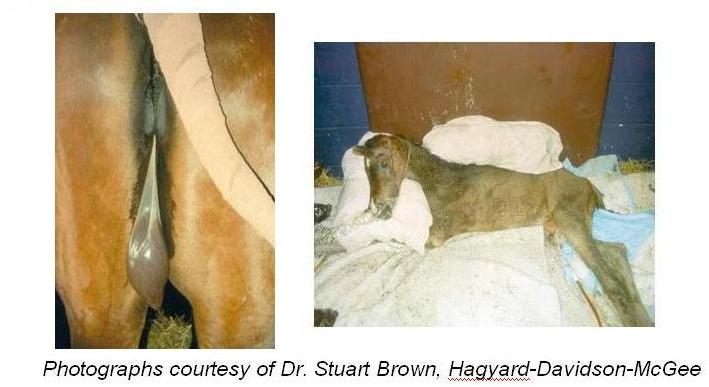

Figure 1.Early (left panel) and late Fetal Losses (right panel) of MRLS.

|

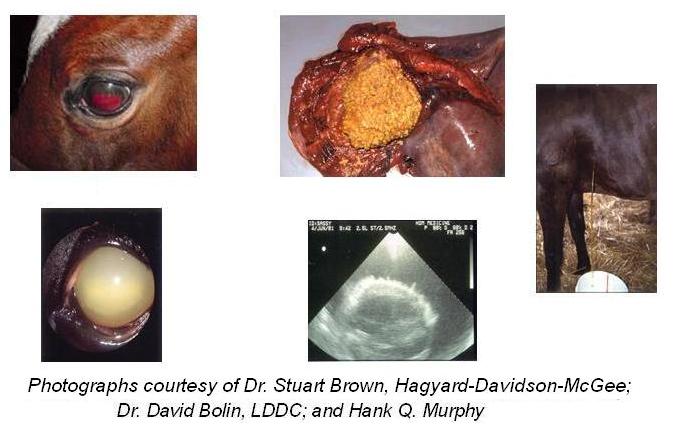

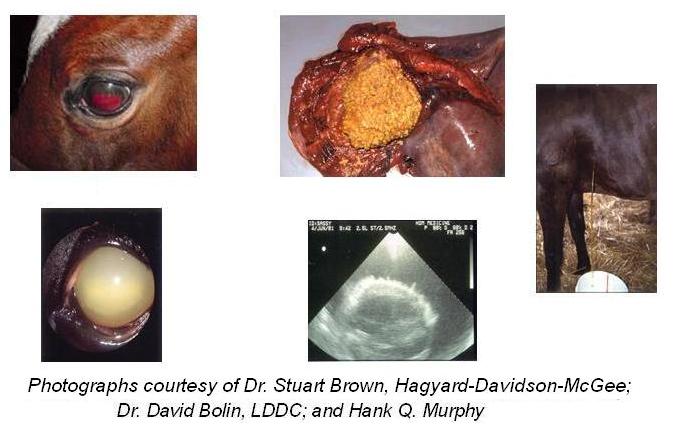

2. THE ANCILLARY SYNDROMES

Soon three ancillary syndromes were recognized and included in the case definition. These syndromes included about 60 coincident cases of fibrinous pericarditis

(epicarditis? Fig 2.), and a slightly smaller number of what can only be described as a unique unilateral panopthalmitis, along with three cases of Actinobacillus encephalitis. These ancillary syndromes, occurring in both male and female horses, were included in the case definition of MRLS.

|

Figure 2. The Associated Unilateral Uveitis (left) and Pericarditis (right) Cases:

|

3. FIRST OBSERVATIONS:EARLY FETAL LOSS (EFL) OBSERVATIONS

MRLS was first identified on

April the 26th 2001

by Dr. Thomas Little, who on that day observed an unusual number of in

utero deaths in 60 day-old fetuses in clinically normal mares that he was ultrasounding for sex

determination. These early

fetal losses were followed by an overwhelming sequence of early and late

fetal losses and, somewhat later, the coincident pericarditis, uveitis

and encephalitis syndromes, occurring in very much smaller numbers in

horses of all ages and sexes were identified.

4. THE PATHOLOGY OF THE LATE TERM FETUSES

The abortions, and particularly the late-term abortions, showed

characteristic pathology. There

were an increased number of "red bag" presentations with weak

and stillborn foals. Necropsy

evaluation of aborted foals showed inflammation of the amnion, the

umbilicus [funisitis], and the fetal lungs. Bacterial isolates included

a high proportion of alpha streptococci, actinobacillus and many other

isolates, including Serratia. The Early and Late abortion syndromes

peaked on about May 5th 2001, Derby Day, and were essentially over by the end

of May.

5. THE EXCLUSION OF INFECTIOUS CAUSES

Within the first week extensive bacteriological and virological

work, the essential lack of clinical symptoms in affected mares, as well

as the essentially simultaneous appearance of the syndrome across the

Bluegrass

largely excluded an infectious cause. Work

then focused on identifying an environmental toxin or agent as the cause

of the syndrome.

6. THE INITIAL TOXICOLOGICAL EVALUATIONS

Within two weeks toxicological investigations had ruled out

nitrate/nitrite toxicity; work then focused on toxins with reproductive

associations; additionally, because of a coincident unusually intense

infestation (plague?) of Eastern Tent Caterpillar (ETC, Malacosoma

americana), the possibility of an association of the syndrome with

the black cherry tree/Eastern Tent Caterpillar biological system was

very carefully evaluated.

7. CLUE #1: THE TIME

AND PLACE ASSOCIATIONS WITH THE CATERPILLAR

Within three weeks preliminary field

investigations by Dr. Jimmy Henning of the Univ. of Kentucky College of

Agriculture pointed to a close association between the presence of black

cherry trees/Eastern Tent Caterpillars and MRLS. Additionally,

preliminary toxicological evaluations suggested increased concentrations

of cyanide in the hearts of some LFL fetuses. The

association of MRLS with presence of the caterpillar was later confirmed

by a rigorous epidemiological survey by Dr. Roberta Dwyer of the

Gluck

Equine Research Center and her

associates (Dwyer et al., 2003).

These

early findings were critically important, because they focused attention

squarely on the caterpillars, which were present in enormous numbers at

many locations in central

Kentucky at the time of the MRLS outbreak.

|

|

Figure 3a.The large numbers of caterpillars during the

outbreak.Here they cover a water bucket.

Figure

3b.The Eastern Tent Caterpillar

|

8. CLUE #2: THE BARBED SETAE

ON THE CATERPILLARS

The early focus on the caterpillar led

Mrs. Pat Van Meter and me to examine them under the Electron

Microscope at about the time of the 2001 outbreak (Fig 3c)). We

noted, in passing, the barbed nature of the very fine setae that

cover the exterior of the caterpillar and we also noted that in

some caterpillar species these setae are venomous and extremely

effective offensive weapons. Although

not specifically recognized as such at the time, these were

critically important observations.

|

Figure 3c.Barbed setae

|

|

9. THE

ENVIRONMENTAL TOXIN HYPOTHESIS

The search for the cause of MRLS at first focused on candidate

environmental toxins, at least in part because Eastern Tent Caterpillars

were unavailable, being out of season. Over

the next nine months rigorous evaluation of the possible roles of plant

estrogens, mycotoxins, ergot alkaloids and Hemlock alkaloids failed to

produce any evidence suggestive of a role in MRLS. The

possible role of cyanide in MRLS was very carefully examined because of

the close association of the Eastern Tent Caterpillar with cyanogenic

Black Cherry trees. Rigorous

experimental evaluations failed to show any association between cyanide

and MRLS (Camargo et al., 2002; Dirikolu et al., 2003). Additionally,

vigorous efforts to induce abortions with a variety of toxins, including

cyanide and mandelonitrile (an intermediate in the release of cyanide

from cherry leaves) and a number of other candidate toxins failed, each

and all.

10. SPRING 2002: RETURN OF THE CATERPILLARS AND

EXPERIMENTAL

AND FIELD ABORTIONS

Return of the Eastern Tent caterpillar in spring 2002 showed that

exposure of early pregnant mares to Eastern Tent Caterpillars rapidly produced

early and late fetal losses, and the abortions closely resembled field

MRLS (Webb et al., 2004). By May 2002 it was

therefore clear that MRLS was very closely associated with the

Caterpillar itself; the question then became how the caterpillar, or

factors associated with the caterpillar, produced the abortions.

11. CLUE #3: RAPID ABORTIONS IN THE 2002 LATE FETAL LOSS

EXPERIMENT:THE BACTERIAL ABORTION THEORY

Towards the end of the 2002 ETC season we administered 50 g/day of

Northern Michigan ETC by intubation to Late Term pregnant mares. The

first abortions occurred very rapidly, within 72 hours, suggesting to us

that the primary driving event in the abortions was most likely

bacterial proliferation in the fetus and/or fetal membranes. We

therefore abandoned the toxin hypothesis and review of this changed

etiology for the abortions and the well established tissue penetrating

capabilities of barbed caterpillar setal fragments led us virtually

immediately (July 10th, 2002) to the Setal/Septic Penetrating

Setal Emboli Hypothesis of MRLS.

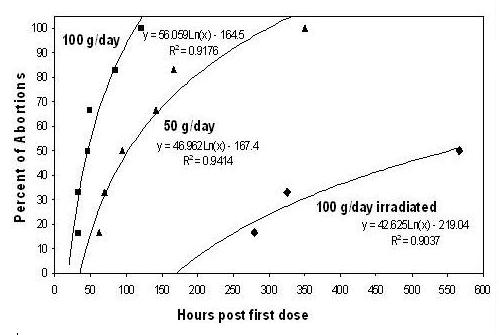

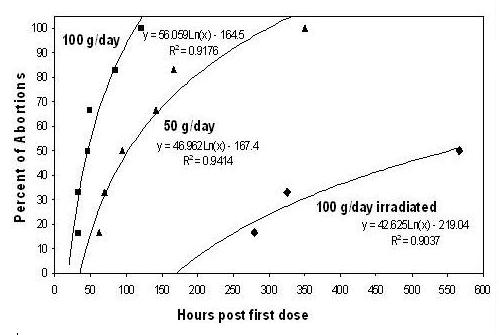

Figure

4. CLUE #2:

Very

rapid time course of abortions following dosing of mares with 50 (02)

and 100 (03, nonirradiated or radiated) grams of Eastern Tent

Caterpillars (ETCs) per day for 10 days. The solid lines are

the best fit regression for the data points. The calculated x-axis

intercepts (apparent lag times) are 20 (100g), 37 (50g), and 193

hours (100g irradiated) after the first dose of ETCs.

|

12. CLUE #3,

2002: BARBED SETAL FRAGMENTS: THE

SEPTIC

PENETRATING SETAL EMBOLI (SPSE) HYPOTHESIS OF MRLS

Considering the barbed setae of the caterpillars, we proposed that

MRLS results from movement driven intestinal penetration by barbed setal

fragments, with their associated bacteria (septic penetrating setae),

followed by blood vessel penetration and hematogenous redistribution of

a proportion of these setal fragments, now forming "Septic Penetrating Setal Emboli" (Tobin et al., 2003, 2004). Systemic

distribution of such embolic setal fragments would follow cardiac

output, as is well described and understood with regard to drug

distribution. These septic setal fragments would then randomly lodge in

distant tissues, and their retained structurally based ability to

penetrate moving tissues would allow them to distribute their bacterial

contaminants in any moving distant tissue in which they lodged. Significant

pathology would result only if the penetrated tissue was poorly

protected immunologically. A

reduced local immune response was, and is, a critical part of the

proposed pathogenesis.

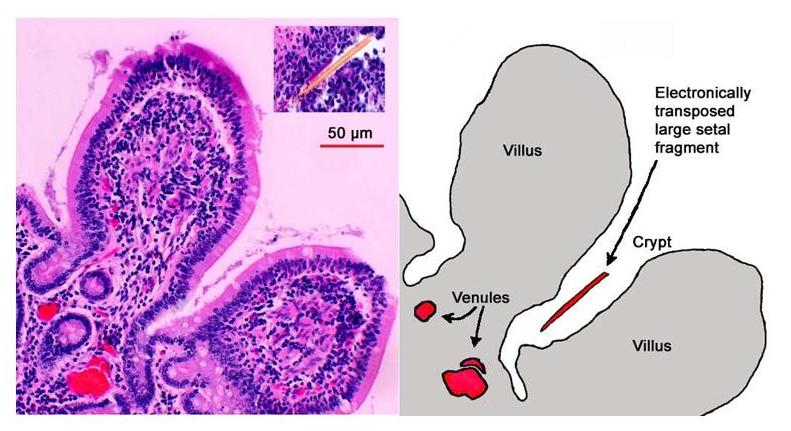

Figure 5.Schematic Construct of Intestinal wall and Intestinal Venule Penetration by Barbed Setal Fragment.

|

13. THE CRITICAL ROLE OF

TARGET TISSUE MASS AND

REDUCED

IMMUNE RESPONSES

The late term fetus is the largest mass of

immunologically poorly protected tissue in the mare. As

such, it is a large and vulnerable target, explaining the unusually

rapid onset of our experimental late term fetal losses. The

early fetus is a much smaller target and therefore less likely to be

"hit,"

but an equally vulnerable target once hit. The

eye is a very small target indeed, explaining the very small number of

affected eyes. Additionally,

the uniquely unilateral nature of the uveitis cases is entirely

consistent with and requires the discrete, quantal, and very small number,

nature of the proposed triggering septic penetrating setal emboli

insults.

13.1. INITIAL RECEPTION OF THE SPSE / MRLS HYPOTHESIS

This "septic penetrating setal emboli" hypothesis as a

proposed mechanism for MRLS was conceived on or about July 10th 2002. It was communicated to selected colleagues within hours and within

days to selected administrators; it would be fair to say that its

reception was unenthusiastic, to the point that its presentation at many

levels was perceived as being discouraged.

14. THE CLINICAL SIGNATURES OF THIS

PROBABILISTIC MECHANISM

14.1. THE EFFECT OF TARGET

SIZE

This proposed pathogenesis depends on the

statistical probability of a distant tissue penetration event occurring

for any given poorly immune protected tissue. As set forth above, it was immediately

clinically obvious that the

actual size (target size) of the immunologically poorly protected target

would influence the probability and therefore the rate at which any

clinically effective septic setal “hit” (or clinically observable

result) would occur. These

factors immediately explained the rapid onset of the LFL experimental

abortions, given the large size of the Late Fetus, which on a weight

basis receives at least 15% of the mare’s cardiac output. The early term fetus is much

smaller and receives proportionally

much less cardiac output. The early term fetus is therefore

statistically much less likely to receive a setal “hit,” thereby

explaining the much slower rate of occurrence of the EFL experimental

abortions. Indeed, very

early fetuses were perceived as being protected from MRLS, likely a

result of their very small target size. The single eye is a very small target indeed, explaining the

relative rarity of the single eye events and the complete lack of any

double eye events. We were

soon, however, to be presented with additional and very compelling

statistical evidence of the probabilistic mathematics underlying MRLS,

namely a unique mathematical signature called Accelerated Failure Time

(AFT).

|

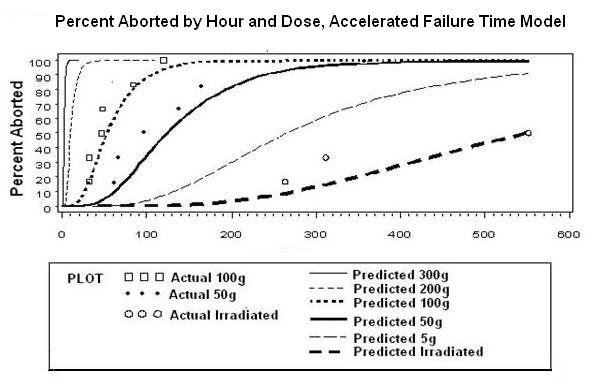

Figure 6. The Mathematical model of MRLS -- Actual abortion rates following dosing with Eastern Tent

Caterpillars |

|

|

Accelerated

Failure Time (AFT) analysis of MRLS

Assumed

that time until abortion has a log-normal distribution a

survival model that well fits the data is an Accelerated

Failure Time Model. The model takes the form:

This

model includes an intercept term (β0)

and an error term (σεi). Ti is

the time that abortion occurs for individual i, and

β1 through

βk are

coefficients for covariates that might affect abortion time.

|

14.2. THE UNUSUAL

PROBABILISTIC MATHEMATICS UNDERLYING

MRLS:ACCELERATED FAILURE TIME ANALYSIS

Further evidence for the unique

probabilistic mathematics underlying MRLS became apparent as follows. On Memorial Day weekend of 2003 we

plotted

the

individual time courses of each of the 2002 and 2003 LFL experiments (Figure 4). The

plotted time courses of the three individual sets of MRLS

abortions in Figure 4 yielded a clear cut family of time course curves. Each

curve clearly fit a smoothly defined exponential rate from the first to

the last abortion; however, and most

unusually, each curve appeared to commence after a specified “lag

time,” and this lag time appeared to be related to the rate at which the

abortions occurred. We took

Figure 4 to Dr. Marie Gantz of the Dept of Statistics,

suggesting that we had half of the equation for MRLS, and requesting

that she provide a factor describing the lag times and we would have the

complete equation for MRLS. Dr.

Gantz pulled the required equation "off the shelf," a probabilistic

mathematical analysis called Accelerated Failure Time analysis (Fig 6). As set forth in Figure

6, the time course of MRLS LFL abortions closely follows this very

unusual probabilistic

mathematical model, entirely consistent with the probabilistic nature of

our proposed Septic Penetrating Setal Emboli model/hypothesis of MRLS

(Figs 4 and 6, P: <.0001 .0052 <.0001).

In lay terms, what this model

says is that it is the rate at which the setal distribution events occur

that determines the speed of onset of an MRLS event. If exposure to caterpillars is high, and the rate of setal

penetration/ distribution events is high, then the lag time is minimal

and the onset of occurrence of MRLS abortions is very rapid. On the other hand, if exposure to

the caterpillars is low, then the

rate of setal penetration (or entry into affected tissues) is low, the lag

time is long and the onset of the first MRLS event is much slower,

taking days to

weeks or longer, as set forth in Fig 6 above.

14.3. THE

EXPONENTIAL DOSE / TIME RESPONSE

RELATIONSHIP FOR MRLS

The second important mathematical

characteristic of this type of mechanism is that the initial intensity of the

response, in this case the rate at which the abortions occur, is

exponentially related the dose. Thus when exposure to the caterpillars

is very high, the lag time is very short, the abortions onset very

rapidly and are closely linked in time and place to the presence of the

caterpillars, as occurred in Kentucky in 2001, and which constituted clue

#1, above.

On

the other hand, when exposure to the caterpillars is low, the onset of

the abortions is delayed, their number is greatly reduced, and the

delayed abortions may occur out of phase with the presence of the

caterpillars. Additionally,

horses in

Kentucky are unlikely to be exposed to caterpillars for more than the short ETC

caterpillar migration season, about two weeks or so in

Kentucky. These unusual

characteristics of the Kentucky caterpillar driven abortions explain

both the exceptional intensity of the 2001 Kentucky ETC related abortion

storm and the fact that these abortions, although previously identified

as a discrete unexplained class of abortions, had never previously been

recognized as being related to (or caused by) the caterpillars.

In sum, these data show that

experimental and field cases of MRLS follow a virtually unique

probabilistic mathematical model called Accelerated Failure Time

analysis, which analysis is entirely consistent with the Septic

Penetrating Setal Emboli hypothesis and our proposed underlying

probabilistic mathematics of MRLS (Fig 6). These

findings in the summer of 2003 enabled us to submit for publication our

first formal toxokinetic/statistical analysis of MRLS (Sebastian et al.,

2003) and then to add,

while this manuscript was in press, a summary description of its septic

penetration setal emboli pathogenesis. Soon thereafter, this

publication was followed by the

full septic penetrating setal emboli hypothesis paper (Tobin et al.,

2004).

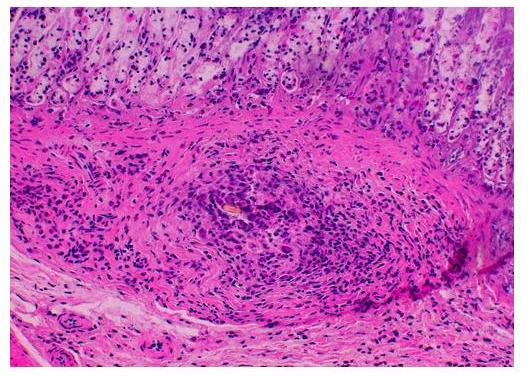

15. Fall O3: IDENTIFICATION OF INTESTINAL

MICROGRANULOMAS

CONTAINING SETAL FRAGMENTS

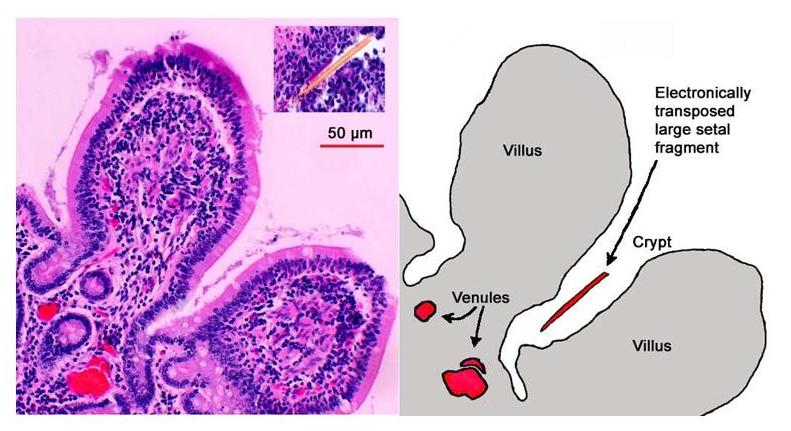

Figure 5 is a construct from our

2004 paper designed to communicate our visualization of blood vessel

penetration by a septic penetrating setal fragment. What

Fig 5 does not address is what happens to the many septic penetrating

setal fragments (SPSF) that enter the intestinal tract and do not enter a blood

vessel. Our hypothesis might

suggest that at least some if not all of these SPSF should work their

way through the intestine to its peritoneal surface and cause

peritonitis, which we were fully aware was not occurring. This

question was the next MRLS conundrum to be answered.

In we understand the late

summer of 2003 a colleague working on a pig model of MRLS necropsied

some pigs which had been dosed for several weeks with ETC. Necropsy of these ETC dosed pigs showed evidence of a very large

number of intestinal setal penetrations in the form of microgranulomas

containing setal fragments in the intestinal tract, fully consistent

with our setal hypothesis of MRLS. Discussing

these rumored findings with another colleague, Dr. Terry Fitzgerald of

Cortland University, he noted that they had made similar observations on ETC-dosed rats

(Fig 7), which slides he immediately shared.

These setal microgranulomas

are interesting, because it is the microgranulomas, small enough in and

of themselves, which had caught the attention of the pathologists. In the center of each of these microgranulomas

was a much smaller

setal fragment. These are,

of course, our postulated “septic penetrating setal fragments”, that

drive MRLS, each caught and immobilized in a little connective tissue

microgranuloma capsule and presumably being slowly degraded. In any event, they are no longer “penetrating” and present

little or no further risk to the animal [or to us]. And

this, of course, is presumably how our intestinal tracts protect us from

having small barbed fragments fully penetrate our intestinal tracts and

induce peritonitis, presumably an anciently evolved digestive tract

protective mechanism. The answer to our intestinal penetration conundrum

is that the barbed penetrating fragments are isolated and walled off in connective tissue

capsules, and that effectively ends their penetrating

ability.

|

Figure 7.Intestinal Microgranuloma in an ETC dosed Rat containing an ETC Setal Fragment at its Center. Courtesy of Dr. Terry Fitzgerald and Colleagues, Cortland University, Cortland, New York.

|

16. SUPPORTING

INFORMATION:THE PERICARDITIS CASES

The pericarditis cases

are also best explained by the septic penetrating setal emboli

hypothesis. Of all tissues in the body, the contracting heart is

one through which one might expect septic penetrating setal emboli to

migrate/be driven fastest. The central role of the heart in the

circulatory system and its ongoing contractile activity may suggest that

at least 50% of setal fragments entering cardiac muscle will wind up in

the pericardial fluid. Bacteria cultured from the

pericarditis cases are those associated with MRLS, although no bacteria

were cultured from some pericarditis cases. This may suggest loss of

septic contaminants during passage of the septic material through the

cardiac musculature. The pericarditis cases are clearly most consistent

with and best explained by the septic penetrating setal emboli

hypothesis.

There is an interesting contrast between the potential outcomes of

intestinal and cardiac tissue penetration by septic penetrating setal

fragments. In the intestine, penetrating setal fragments are

rapidly “walled off” and thereby neutralized. This is

presumably an ancient intestinal defensive strategy designed to prevent

the potentially lethal outcome of peritonitis resulting from intestinal penetration

by barbed structures. Given the importance of preventing setal

penetration, it seems likely that this local “walling off” process

is accompanied by a reflex local reduction in intestinal contractility

in the affected area. On the other hand, such a strategy is not

available in the heart, where fragment movement through cardiac tissue

would presumably be much faster than through the intestinal wall and a

local reduction or cessation in contractility is a much less viable option.

17. SUPPORTING

INFORMATION: LACK OF CLINICAL

SIGNS

IN AFFECTED MARES:

An unusual aspect of MRLS was the lack of clinical signs in

affected mares and the failure to culture bacteria from the bloodstream

of MRLS mares.The unique

eye data allowed us to estimate the number of circulating setal

fragments in MRLS mares.It

appears that the number of setal fragments actually distributing in an

MRLS mare is very small, likely less that ten/day in field cases.This finding explains the essentially complete lack of clinical

signs in affected mares and the practical inability to culture bacteria

from the blood of clinical and experimental MRLS mares. In lay terms, in MRLS at least, there are simply too few setal

fragments circulating to produce an observable clinical response in the

mare herself.

18.

SUPPORTING

INFORMATION:

UNIQUE

PLACENTITIS OF MRLS:

More recently, the placentitis

associated with MRLS has been formally recognized by pathologists as

unique and clearly distinguishable from the classic and well described

ascending and hematogenous placentites, and also, we believe, fully

consistent with the unique SPSE mechanism underlying MRLS.

19. SUPPORTING INFORMATION: OTHER

CATERPILLAR DRIVEN

ABORTION EVENTS

An obvious and early prediction from this

proposed pathogenesis is that mechanically and bacteriologically equivalent barbed setal

fragments or analogous structures from any source should

reproduce the syndrome. As of January 2013, the world score for

caterpillar related abortions is, to our knowledge, as follows:

19.1.

KENTUCKY

Caterpillars have produced

numerous field abortions, MRLS in central Kentucky and

adjacent states (2002, 03) and in

Florida (2006). Also, Eastern

Tent Caterpillars from Kentucky and Northern Michigan

have been shown to be fully abortigenic in experimental situations.

In a challenge experiment in Kentucky, reported in 2004, one of four

pregnant mares exposed to Gypsy Moth Caterpillars aborted, although we

must note that the investigators chose to distinguish between this

single "GMC" related abortion and classic MRLS abortions.

19.2.

FLORIDA AND NEW JERSEY, 2006

In Florida, one of two pregnant mares exposed to high densities of Walnut

Caterpillars (Datana integerrima) aborted within one week, and

the second aborted three months later.

19.3.

AUSTRALIA, 2005

Processionary caterpillars (Ochrogaster

lunifer) were seen in association with field abortions in the Australian

Hunter Valley area (March 2005), and soon thereafter (August

2006) these caterpillars were

reported to be abortigenic in experimental tests. In

point of fact, the principal investigator in this matter was reportedly at first

reluctant to consider the possibility of caterpillar

involvement in these equine abortions. Following the suggestion of

an Australian horse farmer who had suffered significant abortion related

losses, the Australian investigator contacted our research group and

our suggested approach to the described abortion matter was unequivocal.

In our opinion,

the described syndrome was remarkably similar to MRLS, and as such, our

recommendation was, caterpillar experiments first, any and all other

experimental approaches, second. The suggested caterpillar

administration experiments were performed, and the caterpillar

administrations rapidly reproduced abortions. This syndrome, which the

Australians named

Equine Abortion and Fetal Loss (EAFL) is now recognized as being closely

related to and broadly similar to MRLS (Cawdell-Smith et al., 2012;

Todhunter, et al., 2009).

19.5. AFRICA, 2013, CATERPILLARS AND CAMEL ABORTIONS

It

is said there is nothing new under the Sun. Just recently,

researchers investigating the causes of abortions in camels reported that the Sahrawi (literally “people of the desert”) of the

north-western Sahara have long known of the association between

caterpillar ingestion and camel abortion (Volpato

et al., 2013). Though mentioned as a possible cause of camel abortions

by Bizimana in 1994, African caterpillars

have until now received little or no recognition by the scientific

community as abortifacients. The Sahrawi pastoralists are nomadic people who are dependent on camels

for their livelihood. Among

these cultures, it has long been traditional knowledge that a

caterpillar-borne reproductive loss syndrome exists. The Sahrawi people call this “duda,”

which is an Arabic name

for “caterpillar.” Duda

in camels presents many similarities to Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome

(MRLS), suggesting a similar pathogenesis of the disease.

Caterpillars affecting mares and camels are both of the family Lasiocampidae.

The

caterpillar of MRLS (the Eastern Tent Caterpillar) is a hairy caterpillar

with barbed setae. The

caterpillar affecting Sahara

camels is known by the Sahrawi as shedbera,

and is described as a hairy caterpillar. Unfortunately because of the absence of an identified adult moth, the exact species of the Lasiocampidae caterpillar has yet to

be classified. Family

Lasicampidae larva are

generally densely hairy, feed on foliage from trees, and may build

communal tents that contain the caterpillar’s hairs and setae.

Female moths of these species lay a large number of eggs which,

if the environmental conditions are favorable, may lead to outbreaks of the

caterpillars.

Both Duda and MRLS outbreaks

are associated with large numbers of caterpillars in the environment.

When conditions are such, both horses and camels are likely

to ingest caterpillars while foraging. With Duda, the caterpillars are associated with Acacia

trees which Western Sahara camels feed on, as these trees may be

the only green pasture available. In

the

US, MRLS has been associated with environmental conditions that cause

greatly increased numbers of Eastern Tent Caterpillars in trees and

pastures where mares graze. Sahrawi

pastoralists differentiate duda as the cause of abortions in camels from

other causes based on their sudden and episodic patterns of abortion

storms associated with an abundance of shedbera caterpillars on Acacia foliage.

Like MRLS, abortion is the

primary clinical sign of Duda. The clinical signs associated with

Duda

include, in pregnant camels, abortions and uterine prolapse. Calves that are born with

Duda show weakness, red eyes, hair

falling out, astasis and incoordination, joint effusion, swelling

of lymph nodes, and diarrhea. Sahrawi

people are clear that duda is “born

with the calf”, meaning it is not caused by an external agent

after birth. These clinical

signs of duda share similarities with the clinical signs and

presentations of MRLS. Adult

camels who are not pregnant do not show clinical signs of duda, even

when ingesting the caterpillars, again similar to MRLS.

Sahrawi herders are well aware that

it is difficult for them to prevent duda, as the only means of

prevention of this syndrome would be to stop the ingestion of foliage. As

caterpillars may outbreak suddenly on the main foraging source for

camels, it is difficult for the herders to prevent ingestion of

caterpillars by grazing camels. The Sahrawi people also do not have an effective treatment for

weak affected calves born during a duda outbreak, and most of the

affected calves die. Photographs

of the duda caterpillar reveal

a remarkable similarity to the Eastern Tent Caterpillar.

Eastern Tent

Caterpillar |

Duda Caterpillar among the thorns of the Acacia

tree. (Volpato

et al., 2013) |

20. CONCLUSIONS, JANUARY 2013

We believe that only satisfactory

hypothesis offered to date to explain the unique constellation of clinical

syndromes that comprise MRLS

1. the etiology of each of the four MRLS syndromes

2. the unique

probabilistic mathematics underlying MRLS

3. the unique epidemiological presentation

4. the unique pathogenesis

5. the gross histopathological and bacteriological characteristics of

MRLS

6. the predicted and similar now-emerging caterpillar-related abortions in

horses and most recently in camels

is the Setal/Septic

Penetrating Setal Emboli hypothesis of MRLS.

We also respectfully

note that this hypothesis is without precedent in the biomedical

literature.

A

detailed presentation of this hypothesis is available for viewing in a

web slide show

(Tobin 2005) which was first presented at the July 2002 Bain-Fallon symposium in Gold

Coast,

Australia.

While the presentation has

since been expanded and updated, it retains substantial portions of the

first public presentation of the Septic Penetrating Setal Emboli Hypothesis of MRLS made in Australia

in 2002.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

REFERENCES

Adkins, P. (2005) Tracking the source of mare reproductive

loss syndrome. Equus, January, pp 46-9.

Bizimana, N. (1994) Traditional

Veterinary Practice in

Africa. Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammernarbeit.

pp 348-9.

Camargo, F., Dirikolu, L, Sebastian, M., Hughes, C., Crutchfield, J.,

Harkins, J.D., . Boyles, J., Troppmann, A., McDowell, K., Harrison, L.,

Tobin, T. (2002). The toxicokinetics of cyanide and mandelonitrile in

the horse and their relevance to the Mare Reproductive Loss

Syndrome. Proc 4th International Conference of Racing Analysts

and Veterinarians Orlando, FL.

Cawdell-Smith AJ, Todhunter KH, Anderson ST, Perkins NR,

Bryden WL.(2012) Equine amnionitis and fetal loss:

mare abortion following experimental exposure to Processionary

caterpillars (Ochrogaster lunifer). Equine

Vet J.44(3):282-8.

doi:

10.1111/j.2042-3306.2011.00424.x. Epub 2011 Aug 5.

Dirikolu L, Hughes C, Harkins D, Boyles J, Bosken J, Lehner F, Troppmann A, McDowell K, Tobin T, Sebastian MM, Harrison L, Crutchfield J, Baskin SI, Fitzgerald TD. (2003) The toxicokinetics of cyanide and mandelonitrile in the horse and their relevance to the mare reproductive loss syndrome.

Toxicol Mech Methods. 13(3):199-211.

Dwyer, R.M., L.P. Garber, J.L.

Traub-Dargatz, B.J. Meade, D. Powell, M.P. Pavlick and A.J. Kane. (2003).

Case-control study of factors associated with excessive proportions of

early fetal losses associated with Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome in

central Kentucky during 2001. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 222:

613-619.

Neundorf, F. (2007) Caterpillars are aborting our

mares. Australian Performance Horse, January, pp 56-8

Sebastian M, Gantz M, Tobin T, Harkins J, Bosken J, Hughes C, Harrison

L, Bernard WV, Richter D and Fitzgerald TD. (2003) The Mare Reproductive Loss

Syndrome and the eastern tent caterpillar: A toxicokinetic/statistical

analysis with clinical, epidemiologic, and mechanistic implications. Vet

Ther,4(4):324-339.

Tobin, T. (2002) MRLS and associated syndromes: toxicological

hypotheses. Proceedings of the First Workshop on Mare

Reproductive Loss Syndrome, eds Powell, DG, Troppman, A., Tobin, T.,

University of Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station. Lexington,

Kentucky, p 75.

Tobin T, Harkins JD, VanMeter PW, Fuller TA: (2004) The Mare Reproductive Loss

Syndrome and the Eastern Tent Caterpillar II: A Toxicokinetic/Clinical

Evaluation and a Proposed Pathogenesis: Septic Penetrating Setae.Int. J

Applied Res in Vet Med, 2(2):142-158. http://www.jarvm.com/articles/Vol2Iss2/TOBINJARVMVol2No2.pdf

Tobin, T (2005) Mare reproductive

loss syndrome (MRLS) and the eastern tent caterpillar (ETC): a

toxicological / clinical investigation and a proposed pathogenesis;

septic penetrating setae. Available for viewing on-line as a powerpoint

presentation at http://thomastobin.com/mrlspp.htm

Todhunter KH, Perkins NR, Wylie RM, Chicken C, Blishen AJ, Racklyeft DJ, Muscatello G, Wilson MC, Adams PL, Gilkerson JR, Bryden WL, Begg AP.

(2009) Equine amnionitis and fetal loss: the case definition for an unrecognised cause of abortion in mares.

Aust Vet J. 87(1):35-8.

Volpato G, Di Nardo A, Rossi D,

Saleh SM, Broglia A (2013) 'Everybody knows', but the rest

of the world: the case of a caterpillar-borne reproductive loss syndrome

in dromedary camels observed by Sahrawi pastoralists of Western Sahara.Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine.9(5)

(10

January 2013) http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/pdf/1746-4269-9-5.pdf

Webb, B.A., W.E. Barney, D.L. Dahlman,

S.N. DeBorde, C. Weer, N.M. Williams, J.M. Donahue and K.J.

McDowell. (2004). Eastern tent caterpillars (Malacosoma americanum)

cause Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome. J. Insect Physiol.

50:185-193.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

FURTHER

READING

1. Proceedings of the First Workshop on Mare Reproductive Loss Syndrome

on the Web: http://www.ca.uky.edu/agc/pubs/sr/sr2003-1/sr2003-1.htm.

A one-page summary of the hypothesis is presented on page 75.

2. For more on MRLS – including caterpillar control, disease

prevention, additional research and archives – go to www.uky.edu/ag/vetscience/mrls/index.htm.

3. A complete listing of scientific articles addressing MRLS and

published by the Tobin research group is located at http://equinetoxicology.com/mrlspubs.htm.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

SUPPORT CREDITS

From the Equine Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Toxicology Program of the

Maxwell

H.

Gluck

Equine

Research

Center,

University

of Kentucky,

Lexington,

KY.

This research was supported by grants from the USDA Agriculture Research

Service Specific Cooperative Agreement #58-6401-2-0025 for Forage-Animal

Production Research, the Kentucky Department of Agriculture, the

Kentucky Thoroughbred Association Foundation, the Horsemen’s

Benevolent and Protection Association, and Mrs. John Hay Whitney.

|